Modifying a Northeaster Dory for Camp-Cruising

More than a thousand CLC Northeaster Dories have been built. I credit the Northeaster Dory's success to the intrinsic qualities of a wooden dory. A dory is a great value for the time and money. The parts-count is low, yet performance is high, thanks to a combination of features perfected in the 19th century. I think we've shipped so many of CLC's Northeaster Dories because I went to great pains to keep the kit simple. Without a lot of filigree and complicated joinery, the "base model" builds quickly and easily, handles great, has plenty of capacity, and will take you a long way.

And builders have been taking them a long way. We hear of unsupported cruises in Maine, Alaska, the Sea of Cortez, and beyond. More or less unmodified versions captured several Class 4 podium finishes in the Everglades Challenge, including a 1st place.

Over the past few years I've seen a surge in the number of Northeaster Dories being modified for overnighting, beach-cruising, camp-cruising, and Serious Sailing in general. I like everything I've seen; some mods have been very clever indeed.

The stock-standard Northeaster Dory with a lug rig. Quick, handy, easy to build, and affordable.

If you're pondering how you might optimize the standard Northeaster Dory for overnight work and/or unsupported activity in rougher water, the priorities should be as follows:

1. Increase flotation and "self-rescue" capability.

2. Create secure storage for overnighting gear.

3. Rearrange the seating to allow sleeping aboard.

4. Swap the daggerboard for a centerboard.

Flotation and Decking

Let's work down the list. Out of the box, the Northeaster Dory is specified to be fitted with foam flotation glued to the undersides of the thwarts. This supplies about 275lbs of buoyancy. Tests show that is sufficient flotation to allow a reasonably athletic crew to right and bail out a sailing version of the Northeaster Dory. Since no other traditional wooden dory design has any additional flotation at all, aside from the wooden hull, this is an improvement. I wouldn't want to try it in really rough conditions, however.

Some years ago I circulated this drawing, showing how dry bags or air bags, strapped securely low in the boat and out to the sides, would make capsize recovery less hairy.

If you're cruising in rough water, the first priority is to make the boat easy to rescue after a capsize. The foam under the seats is sufficient for a self-rescue in smooth water. Drybags, or just airbags, strapped low in the hull are an improvement.

The flotation bag approach is de rigueur in small, open boats, a tactic as old as recreational boating. There are plenty of objections on functional and aesthetic grounds, so I'm not surprised to see some Northeaster Dories being built with decks.

The natural reflex is to span the bow area of the boat with a sheet of plywood, enclosing the hull back to the mast at the level of the sheerline. I wouldn't stop anyone from doing this, but if I were handed an unfinished Northeaster Dory and told to go row and sail the ICW, that's not the approach I would take.

In rough going, the spray off the Northeaster Dory's bow wave generally boards just aft of the mast. A full-height deck forward of the mast adds lots of valuable reserve buoyancy after a capsize, but it probably won't help keep you dry the rest of the time.

When sailing in rough water, spray generally comes aboard over the forward quarters of a small boat, not over the bow. Decking forward of the mast helps a lot with flotation, but won't keep the cockpit dry.

I would drop the decking down to the bottom of the top strake, creating "bulwarks" around the whole perimeter of the boat. This gives you a lot of secure storage. For example, an anchor and rode can live on the deck up forward. You still get nice dry storage areas at the bow and stern.

Here's how I'd optimize my own Northeaster Dory for camp-cruising. The deck runs from bow to stern a few inches down from the gunnels, creating storage compartments and cockpit seating.

This is where it gets tricky. Imagination takes flight, and intricate compartmentalization and joinery can be dreamed up more easily than it can be built.

For the purposes of this article, I've set rigid restrictions: No hull modifications---only parts from a stock Northeaster Dory kit may be used. (Frames are redesigned, and there's an additional bulkhead, but the frames are all located in the same place as the normal ones.) Keep the number of parts to an absolute minimum, accepting some trade-offs to minimize added weight, cost, and build time. Maintain performance.

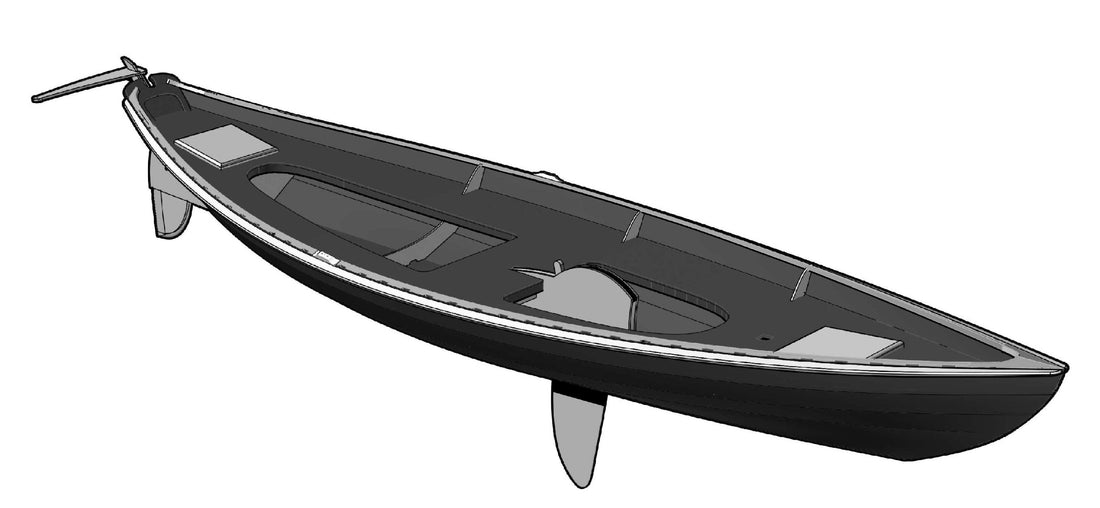

Here's the result:

Modified Northeaster Dory. The deck creates storage and seating. For simplicity, much of the additional flotation is still in the form of dry bags under the seats. The lug rig seems to be the choice of the hard core Dory cruisers. Spacered inwales are another worthy addition...

If I was certain I'd always be solo, perhaps the "forward cockpit" could be decked over, too, becoming sealed storage. You would then, however have no seating for a passenger. You'd also have to sort out how to step the mast in a watertight socket, a challenge even the manufacturers of the venerable Laser and Sunfish have never solved entirely.

But back to priorities: Keep It Simple. Having the the decks and seats at the same height simplifies construction and looks nice.

Bench Seating

In my version, the crew has bench seating. Their butt is higher than their heels. EVERYBODY except me seems to want seating like this in the Northeaster Dory. This feature adds a lot of weight and cost, but that's not my main objection. The problem is that it raises the center of gravity of the crew. Sitting up and out to one side on the bench seat, the skipper's weight exerts powerful righting moment. Great! you say. Except in light air, or a sudden lull, when the lightweight boat lurches to windward. Your own weight is sufficient to capsize a boat in this weight class. Most of the time, the Northeaster Dory likes the crew seated thus:

I won't argue that bench seats aren't comfortable. In light-to-moderate air, however, the Northeaster Dory is happier with the crew weight low and centered in the boat.

I'll take the bench seats because they have a role in my flooded-stability scheme, so enough of that debate.

Left to right: No side benches or tanks; open side benches; and closed "seat tanks."

The drawing above is a comparison of different ways to handle side-bench seating and flotation. On the left we have the standard Northeaster Dory, with no side benches at all. At least the buoyancy foam under the thwarts is low down in the boat, where it will start providing flotation assistance before the hull is completely swamped.

In the middle is how I sketched my proposed camp-cruiser Northeaster Dory. There are watertight bulkheads closing off compartments in the bow and stern, but the middle ten feet of interior has open bench seats and a thwart amidships. This configuration would still be a mess if you swamped the boat, so the idea is that you pack your gear in drybags and strap them under the seats. Positioned as shown, you get plenty of buoyancy, AND MORE STABILITY when swamped.

The drawing on the right is the stock Southwester Dory, the Northeaster's larger sister. As the Southwester can be fitted with an outboard motor, I was obliged by US Coast Guard regulations to provide emphatic reserve buoyancy and "flooded stability." The Southwester Dory has side benches, plus vertical panels on the inboard edges of the seats that create vast airtight volumes. These sealed tanks really limit how much water can be taken aboard in a capsize.

Obviously the latter approach, also employed by capsize-prone racing dinghies, is the safest. So why didn't I suggest that for the Northeaster Dory?

A. The weight of the additional structure. Though two feet longer than the Northeaster Dory, the Southwester Dory has exactly the same payload as the Northeaster. All that extra joinery eats up your useful payload.

B. The complexity of installing it. Those vertical seat faces are tricky to fit unless we do it for you in the computer. The sealed-off cockpit is like building a boat-within-a-boat.

C. The added cost. There's a reason the Southwester Dory costs $1500 more than the Northeaster Dory...

D. Ergonomics. Foot room would be quite restricted if you sealed in the benches in the Northeaster Dory. It's not a problem in the larger, wider Southwester Dory, and the dinghy racers don't care...

Okay, One Complex Luxury:

A pivoting centerboard! Certainly a frequent request. Click here for an explanation for why the standard Northeaster Dory has, and will continue to have, a daggerboard.

The exertions required to fit a pivoting centerboard into this speculative camping version reminded me why I'd never considered it in the first place.

Compared to the daggerboard, the centerboard installation adds cost and complexity to the build. It also requires the center thwart to be placed higher and further back in the boat, neither of which are good for rowing efficiency. It works, though, and I sense that the hardcore camp-cruisers would accept the trade-offs.

Sleeping Aboard

Wooden battens span the rear cockpit seats to create a sleeping platform.

Next problem: a place to sleep. In some locales, you can cruise from beach to beach or island to island and camp ashore. The Northeaster Dory's payload capacity would allow you to camp shoreside in admirable luxury. You could carry a big tent and all of the "glamping" stuff you could want.

The United States, unfortunately, has a shortage of such cruising grounds. A lot of dinghy-cruisers need to be able to sleep aboard because waterfront land is privately owned.

There's just no way to rearrange the Northeaster Dory to create a flat, bunk-sized place down on the floor. The traditional dory hull shape has too much flare for an "offcenterboard" installation, which would clear the center bottom of the hull for sleeping. Leeboards won't work for the same reason. We'll have to live with the centerboard trunk and rowing thwart smack in the middle of the boat.

The solution? A lightweight bundle of wooden battens, stitched together with webbing so that they can be rolled up like rabbit fencing. Unroll the battens and they'll span the rear cockpit benches, forming a sleeping platform large enough for a single average adult. (Need to sleep two onboard? I direct you to the Southwester Dory, Guider, or PocketShip.)

I don't know who originated this trick, but I first saw it 30 years ago in John Glasspool's book, Open Boat Cruising.

A Look at Some Similar Boats

The Northeaster Dory's many appealing features include simplicity, low cost, and quick construction. If you've read this far, you might have a sense of the trade-offs. A major round of modifications adds complexity, expense, and labor to a simple boat.

On that note, it's worth looking at a few of the Northeaster Dory's drafting board cousins, all of which were designed as safe, serious camp-cruisers.

The simple Skerry Raid (top) and its sophisticated descendant, the Guider (bottom), shown to scale.

The Skerry Raid (top drawing, above) is an interesting study in this context. John Guider approached me about using a stock CLC Skerry to row and sail the 6500-mile Great Loop. The standard Skerry bears a close resemblance to the Northeaster Dory, both in hull shape and interior layout. Concerned about the many rough passages he would encounter, but constrained by John's budget and skill, I sketched some modifications that would be effective but cheap and simple. The Skerry gained a deck with big watertight compartments, and side decks under which flotation foam was fitted. The daggerboard was swapped for a centerboard.

The Skerry Raid, as the modified Skerry came to be called, fulfilled its mission. John Guider completed the Great Loop (and several other ambitious voyages) without serious mishap. John thought he'd camp on shore every night, so there was no provision for sleeping aboard, a feature of the design he came to regret. Nor is there really room for a passenger. Nevertheless, 15 or 20 of them have been built so far.

John announced a bid for the Race to Alaska, and the little Skerry Raid seemed unsuited to that very cold, very rough itinerary. I persuaded him to let me design a cruising dinghy from a clean sheet. In appreciation for his patience, I named the all-new design the "Guider." The Guider is a big, rugged, back-country cruising dinghy. It's heavy, carries lead ballast, and features more than a dozen watertight storage compartments. There is plenty of room to sleep two big adults beneath a cockpit tent. A combination of exhaustion and mishap scuppered John's 2019 Race to Alaska attempt. But the boat's performance during the Race, and extensive testing here on the Chesapeake, have proven the capability of the design, and quite a few have been built.

Designed and assembled without compromise, the Guider is complex and expensive. It's a good illustration of where you end up when you're not too concerned about parts-count and budget.

The Southwester Dory, with optional outboard well.

Which brings us to the Southwester Dory. My design brief for this boat was to retain the Northeaster Dory's good looks and easily-driven hull, but add bench seats, a pivoting centerboard, and the option of an outboard motor installation. I gave the boat a yawl rig, a feature many Northeaster Dory builders ask about.

To carry the weight of these additions, I had to add almost two feet of length and eight inches of beam to the Northeaster Dory. The Southwester Dory is straightforward to build and easy and comfortable to sail. In kit form it costs some 60% more than a Northeaster Dory, and we ship about 10 Northeasters for each Southwester we sell.

Does modifying and outfitting a Northeaster Dory escalate that simple design's cost and build-time into Southwester Dory territory? Not quite. If the smaller boat's low cost of entry and easy construction get you out on the water and off to that distant beach sooner, well, that's why it exists.

But if you want a look at what happens when you undertake a thorough and careful expansion of the Northeaster Dory's capabilities, you end up with the Southwester Dory.

Note: The camp-cruising version of the Northeaster Dory is a speculative design. The drawings you see on this page are all that exist. We'll monitor interest, but at present you can't order a kit or plans for the modified Northeaster Dory.