Russell Brown on Proas

Russell Brown designed and built his first proa---a multihull sailboat with one big hull and one little hull---as a teenager in the 1970's and promptly went to sea in it, cruising the US East Coast and the Caribbean. Adventures ensued. In the decades since, between stints as a professional boatbuilder with a specialty in ultralight racing boats, he's designed and built several more proas.

Russell's one of the most talented boatbuilders I have ever met, and he has the cred to go with my instinct on that. He's worked for BMW/Oracle building America's Cup boats, and worked with multihull god Dick Newick among many others. His humility is even bigger than his talent, though, and he's forthright that he'd prefer to just build boats and go sailing and not hold himself up as a proa know-it-all. Compared to the rest of us, though, he DOES know it all.

After a long period of cajoling, he finally sent me his thoughts on designing, building, and sailing proas.

For the newly initiated, a "Pacific" or "windward" proa is basically a multihull sailboat with a single float or outrigger for stability. Under sail, the outrigger is ALWAYS kept to windward. So in order to tack, you have to exchange bow for stern! Thus proas have two bows and can sail in either direction. –John C. Harris

John C. Harris: You've been building and sailing proas since the 1970's. What is it about proas that has kept you coming back all these years?

Russell Brown: Proas are a wide open playing field from a creative viewpoint. These boats offer an amazing array of potential advantages (and of course, disadvantages) over catamarans and trimarans, but they still have not been widely explored.

One major attraction for me of the Pacific proa is that the concept is, in my mind, as close to structurally perfect as a multihull sailboat can get. In flat water, a proa can be sailed as hard as possible and the structure stays very lightly loaded. Yes, there’s a bit of mast compression (but not much, because of the wide staying base), and a small amount of bending load on the beams, but most of the sailing loads go to the shroud lifting the outrigger.

Adding water ballast in the outrigger doesn’t load up the structure very much, and because it is so far to windward, it doesn’t take very much ballast to keep sailing flat.

Proas are a hell of a lot of fun to sail, but in the end curiosity is what keeps me coming back to them.

JCH: You've got tens of thousands of sea miles in proas, but you've been forthright that proas aren't for everybody. In your mind, what sort of sailor should consider building a proa? (My filter for Mbuli, CLC's 20-foot proa, is that the sailor should have many hours in high-performance sailing craft, particularly multihulls. This will be the filter for Madness, CLC's new proa, too.)

RB: I haven’t thought much about this, having decided long ago that designing proas for other people to build and sail was not for me.

I think that trying to filter clients for such a high-performance sailboat is a good idea, but there will still be people doing crazy things to and with the boats you design. Because proas are still such an unexplored area in the Western Hemisphere it seems that experimentation and craziness are in order, but it creates an awkward position for someone trying to design proas for others.

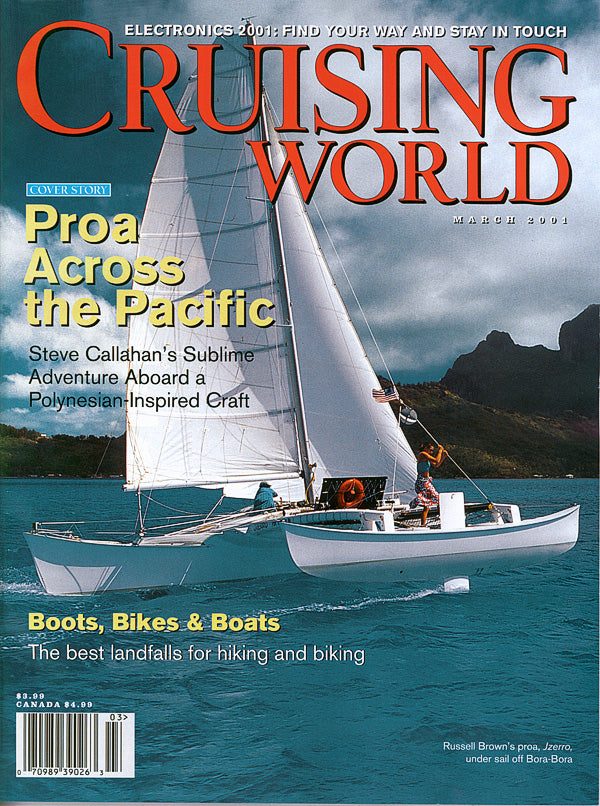

JCH: You've designed and built at least four notable proas, ranging from 30 to 37 feet. Could you give us your recollections and impressions in just a few lines for each of them---Jzero, Kauri, Cimba, and Jzerro?

RB: Jzero was a 30-foot piece of junk that sailed exceptionally well.

Mark Balogh, who sailed a lot on this boat, said basically the same thing, that it was a piece of junk, but that it was in many ways my best design. It was certainly the most bang for the buck having cost about $1200 at the end of my time with it. I don’t know how many miles Jzero went, but it was a lot. That boat was happiest going upwind.

On a 350 mile upwind leg of the 1979 Tradewinds race, Jzero finished 2-1/2 hours behind the leaders: a 60-foot Newick trimaran and a 60-foot Spronk catamaran.

Kauri, 37’, was designed and built as a cruising boat. It wasn’t the prettiest boat around but it sailed better than it looked. This boat was my home for about 8 years and was sailed up and down the east coast seasonally most of those years.

Once, on the way to Bermuda from Florida, my buddy Mike & I sailed through a tropical depression. Actually, we hung on a sea anchor for 4 days of 40 knot head winds. We were pretty comfortable below, talking and sleeping, but had to take turns looking around outside because it took awhile to calm down after looking at the conditions.

Kauri was sold in 1989 to fund the next boat, Jzerro.

Cimba, 38’, was built in 1984 with and for my friend, Lew McGregor. This was the first proa I designed that wasn’t built on a shoestring. A lot of design work went into it and it was a lot better-looking than Kauri.

Cimba was slightly overbuilt. Other things I built during that time were overbuilt too, so it seems like a phase I was going through.

Cimba was caught in a major gale in the Mediterranean just last summer with a family aboard. The boat got a terrible pounding and received some damage to the ama, but did limp into port after a very scary night.

Jzerro, 36’, was built in Port Townsend, WA and launched in 1994. This boat has many similarities with my previous proas, but was lightly and carefully built. It weighs about 3200 pounds. In the fall of the year it was launched, Jzerro sailed a sustained 22 knots on the way to a race.

In 1997, I sailed the boat to Mexico, and back the following year. The boat received quite a thrashing both coming and going, including a 50 knot gale off northern California.

In 2000, Steve Callahan & I sailed Jzerro across the Pacific from San Francisco to the Marquesas islands. Both of us still think of this as the best adventure we have had.

I continued solo from the Cook Islands to Australia and the following year crossed to New Zealand.

I learned more about this kind of proa and what it could do on this trip than I had in all my previous proa sailing.

JCH: You launched your last proa, Jzerro, in 1994 and you've cruised far and wide. If you had the time to design and build a new proa, would you make incremental changes, or would you head off in some other direction entirely?

RB: If I had the chance to build a new proa it would look quite different, but overall I would stick with a similar concept and proportions.

JCH: You've been an active participant in the design of Madness, my stitch-and-glue proa. For the record, how would you characterize your contribution to Madness?

RB: Consultant, I would say.

JCH: How do you feel about proa rudders? At one end of the design spectrum we have the Newick dagger-rudder style, which offers the highest efficiency but is hard to build and has the drawback of deep sailing draft, and at the other end we have a hand-held paddle over the side of a canoe. And a whole lot of ideas in between.

RB: I have seen and tried other steering methods, but the Newick style rudder in a trunk (first used in Cheers in 1967) beats all the others by a mile in my opinion.

“Sideslung” rudders with surface piercing foils are just too problematic for me, unless it’s the hand-held paddle.

The only proa rudders that could possibly be better than the Newick style rudders were designed recently by Dick Newick himself for a large cruising proa. These are kick-up rudders that have many advantages, but also have some technical challenges.

JCH: As with rudders, you can start fights pretty quickly among the proa boffins talking about sailing rigs. It's a big subject, but are there alternatives to the modern sloop rig that you like?

RB: Yes, a cat ketch rig with free-standing masts has appeal. A rig like this would be easier to tack (especially with wishbone booms), and less vulnerable to being caught aback, but the compromise in performance, especially upwind, is not attractive

Dick Newick’s wonderful Atlantic proas, Cheers, Azulao, and Godiva Choclatier had cat ketch rigs. [Atlantic proas keep the float to leeward at all times, rather than to windward. -Eds.]

Jzero raced against Azulao, a 42’ racing proa, in the race mentioned above and was about 18 hours ahead at the finish. Azulao was faster reaching in breeze, but didn’t come close upwind.

There are many things about the sloop rigs I have been using that just seem to work. Yes, it is basically the same rig that has been used on every fast multihull since the Hobie Cat, but on a Pacific proa there are advantages that catamarans and trimarans don’t see.

-The mainsail doesn’t hit the shrouds when off the wind. The main sheet can be dumped when overpowered off the wind (until the mainsail is over the front of the boat)

-The wide slot between main & jib (because the mast is stepped to windward) seems to really help the boat go upwind.

-Because of the very wide staying base there is very little mast compression, so a small mast section can be used.

Jzerro’s mast is a rotating aluminum wing section 3-3/4” x 7 -1/2”, and weighs 160 pounds with all standing and running rigging. The mast on Jzerro is only 36’ long and carries enough sail for all but really light conditions.

Jzerro will reach at 17 or 18 knots in 12 knots of wind.

The multiple self-steering and heaving-to options are worth mentioning too (though the same would be true with a cat-ketch rig). In heavy weather a proa with this rig can be made to steer itself from upwind to a reach. This is an advantage over autopilot steering in that the boat will feather into gusts and squalls instead of taking off like a shot and going airborne while you are trying to relax below.

Hove-to, the boat can be made to park at an angle to the wind and waves or walk slowly to windward and can be trimmed by raising and lowering the rudders and trimming the sheets.

Yes, there are disadvantages to this rig on a proa, such as the work involved in tacking---you have to douse one jib and hoist another---but I’m not quite old enough yet to think about an easier rig.

JCH: Going cruising in proas or other small multihulls requires packing pretty lightly. In the year 2010, do you think there are people who would consider cruising in fast 31-foot boats like Madness that lack heated showers, AC inverters, and private staterooms for six?

RB: I used to own a Tornado catamaran (a 20-foot beach cat) and did some extended cruising on it. This was possibly my favorite cruising boat, so I may not be qualified to answer this question.